Leia Babu

The relationship between China and the African continent has undergone a profound transformation over the past 65 years. Today, many observers describe this dynamic as a form of neo-colonialism, citing resource exploitation and asymmetrical influence. While both China and African governments insist that their partnership is a “win-win,” this assertion remains the subject of considerable debate.

In this article, we will examine the advantages and drawbacks of this evolving alliance to determine whether it truly represents mutual benefit—or a modern version of colonialism.

The roots of Sino-African cooperation trace back to the 1955 Bandung Conference, which sought to unify newly independent nations of the Global South in opposition to the Western and Soviet blocs. The spirit of Bandung continues to be invoked in Chinese rhetoric today. During the era of decolonization, China positioned itself as an ally to emerging African nations, offering political support and economic aid. This strategic engagement paid off notably in 1971, when 26 African nations voted in favor of the People’s Republic of China’s admission to the United Nations—over the Republic of China (Taiwan). This vote was a landmark moment in Chinese diplomatic history, and a clear example of early reciprocal benefit.

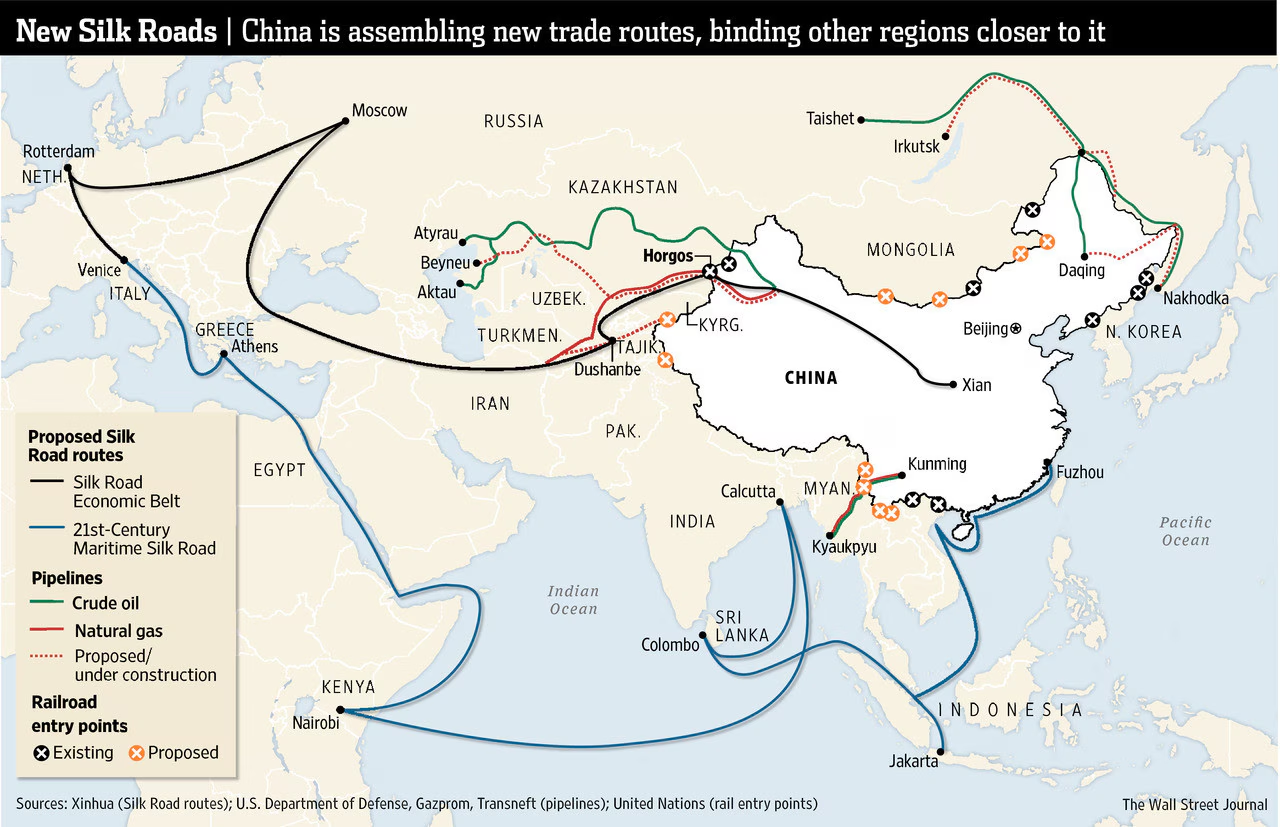

In the 21st century, China-Africa relations have taken on new dimensions. “Chinafrica” now forms a central pillar of China’s vast geopolitical initiative known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), or the “New Silk Roads.” This ambitious project seeks to connect China with Europe, Central Asia, and Africa through expansive networks of road, rail, and maritime infrastructure. Encompassing over 68 countries and nearly 40% of global GDP, the BRI reflects China’s desire to secure export markets, offload industrial overcapacity, and extend geopolitical influence. For Africa, the BRI promises investments in much-needed infrastructure and industrial development.

By 2017, China had become the world’s second-largest economy, and Sino-African trade had reached $143 billion. Although this represented just 3.7% of China’s foreign trade, it accounted for a significant 15.4% of Africa’s. Between 2005 and 2017, China lent approximately $137 billion to African nations, primarily to fund infrastructure and energy projects. However, this influx of Chinese capital has also contributed to mounting debt levels. For instance, by 2018—just two years after the formal launch of the BRI—Mozambique’s national debt had reached 103% of its GDP, with Chinese loans accounting for 17.5% of that figure. The risk of debt distress is real, yet both sides continue to insist that the relationship remains mutually beneficial.

Why then do African countries continue to embrace Chinese investment despite these debt concerns? For Beijing, Africa represents an outlet for surplus capital and industrial production. For African nations, Chinese financing offers a lifeline to accelerate infrastructure development—something many Western institutions are slower or more reluctant to support. Unlike traditional lenders such as the World Bank or the EU, China’s loans often come with fewer political conditions. Moreover, China frequently packages its loans with turnkey infrastructure solutions, deploying its own firms and technical expertise—filling a gap that many African countries desperately need to address.

Nevertheless, this strategy raises questions about long-term sustainability. While China may be less concerned about loan repayment, it often secures its investments through “collateral clauses,” allowing repayment in the form of raw materials or infrastructure control. These arrangements can leave borrowing nations vulnerable to economic and political dependency.

China’s presence in Africa also extends beyond economics. As Joseph S. Nye notes in his 2018 article “China’s Soft and Sharp Power,” China’s global strategy combines both soft power—the power of attraction—and sharp power—more manipulative, opaque forms of influence. Soft power, a term Nye introduced in 1990, refers to the ability to influence others through cultural appeal, values, and policy. In contrast, sharp power relies on tactics such as censorship, propaganda, and information manipulation, particularly within open societies.

China deploys both forms of power in Africa. On one hand, it has heavily invested in cultural diplomacy—funding Confucius Institutes, media outlets, films, music, and academic exchanges. On the other, it has employed more coercive measures, subtly shaping political discourse and public opinion to align with its interests. Nye warns that while democracies must counter sharp power, they must do so without undermining their own credibility or soft power in the process.

Adding complexity to the issue, the relationship between Africa and the West has grown increasingly strained. Historical memory and geopolitical tensions have made Western interventions in Africa susceptible to criticism—often perceived as neo-colonial intrusions or a “return of the colonizer.” In this context, China’s assertiveness can appear more palatable to African leaders seeking investment without political interference.

In conclusion, the China-Africa partnership—often dubbed “Chinafrica”—does offer the potential for mutual benefit. Indeed, China’s engagement goes well beyond infrastructure and finance; it aims to establish a lasting cultural presence and assert its influence on the global stage. More notably, China is making deliberate efforts to reach African populations directly, shaping public opinion and forging new alliances.

Article gentiment envoyé par Mme. Leia Babu.

Commente ou donne ton avis sur cet article.